‘Avatar’ review: Meticulous visuals conceal a thin plot

Texture, texture, everywhere texture. Texture drilled into every frame. Texture etched into every face, layered into every creature, scratched into every machine.

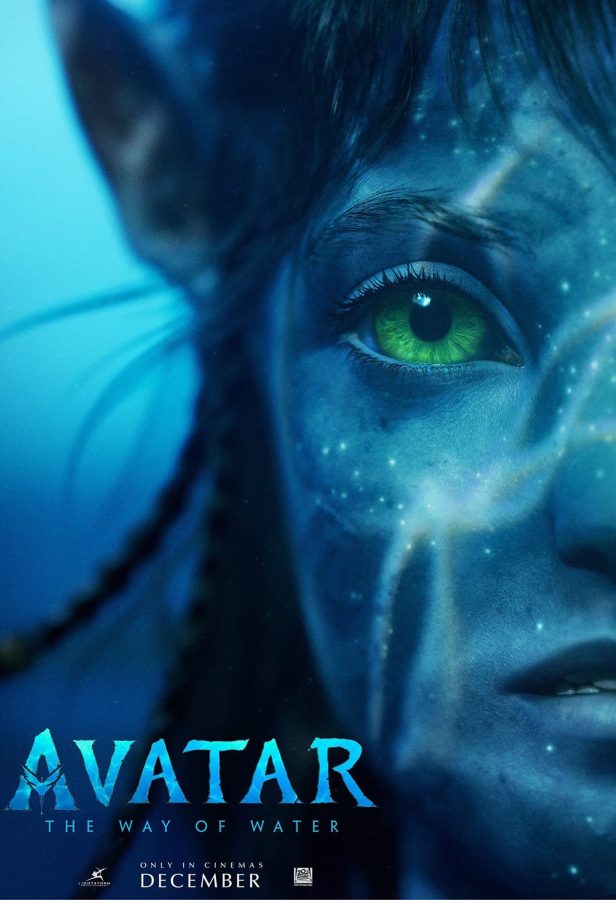

James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water renders the mystical world Pandora in painstaking, delightful detail. Everything seems so real, so undeniable. That $250 million budget? It pays off, at least with the special effects. Big time.

But Cameron’s film, a long-anticipated sequel to the seminal 2009 original, fails to match its enchanting visuals with a compelling story or characters worthy of investment.

Avatar 2 plunges viewers back into Pandora, about 15 years after the first movie left off. Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), the transformed human who leads the Na’vi, has grown a motley family with Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña). Their sundry brood consists of a human boy with complicated parentage who acts like a Na’vi, an adopted girl born from the dead avatar of Grace Augustine (a child played, in a confusing twist, by a digitally de-aged Sigourney Weaver, the actor who created Augustine in the original “Avatar”), and their own three children.

The film opens with a stunning panorama of a peaceful Pandora. The humans, the “sky people,” have left, mostly, leaving in their place an idyllic paradise liberated from human greed and destruction.

But back come the sky people, back come the greed and the warfare and the destruction—except this time with a curious dash of imperialism. Gargantuan ships descend, melting the forest beneath them, charring a tranquil landscape. Black smoke billows up to blot out the sky.

And so it begins. The Na’vi go to war.

But this is not a film about war, not really.

The action pivots swiftly to a new part of Pandora, the distant sea tribes that hold only the barest connection to their forest counterparts. It is here that the bulk of the film takes place. A lengthy second act contains little meaningful conflict and instead serves as Cameron’s excuse to display his arresting technical prowess.

So great is that prowess, so immersive are the cultures Cameron builds from scratch, that the narrative failings fade. The visual constructions—the landscapes and the animals that slice through the water and everything in between—elevate the film past its roadblocks.

But those roadblocks are rooted deep, and though the visuals maneuver past them, they become a problem. Thin, interchangeable characters fill a muddled plot built on illogical foundations. A 192-minute film fails to spend time on developing its characters.

That hurts. Avatar 2 focuses on family, but it’s a skeleton family bereft of connection. It looks like a duck, it swims like a duck and it quacks like a duck—but it doesn’t feel like a duck.

Driving the family’s migration from forest to ocean is the reincarnated Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang), the dead colonel from the original whose memories are transplanted—with typical blockbuster ignorance of narrative obstacles—into an avatar body. Quaritch’s vendetta against Sully pushes the plot forward.

Dissonance arises: The humans purportedly return to Pandora to establish a refuge for the inhabitants of a dying earth, but Quaritch’s raging hate for Sully really fuels the plot. The film presents an in-universe rationale for the humans’ single-minded pursuit of Sully—in comes some military general to explain why Sully’s death is crucial to pacify “the hostiles”—but really it’s all an excuse to position Sully and Quaritch in opposite corners of a universe-sized boxing ring.

In the end, nothing gets resolved. And because the script fails to create fleshed-out characters, there is little narrative tension. There are some pangs, yes, but they derive from the dazzling technical work rather than any attempt at building characters.

You know how the National Geographic channel turns a penguin scuttling for food into riveting theater? Same idea.

Still, Cameron creates something indelible, idiosyncratic. The script alone suffers from the usual trappings of failed blockbusters; the visual product exists on a higher plane.