As shootings mount, district reacts

May 28, 2018

The announcement came shortly before 2 p.m.: This was a lockdown. Across WHS, students and teachers went through the familiar motions—doors locked, lights out and everyone to the back of the room.

But according to several drama students in the auditorium that afternoon, this lockdown had an unfamiliar feel. The teacher that day, a substitute, was unsure how to proceed. The students responded by taking charge. After calming the substitute—the only adult present—they demonstrated how to close the auditorium doors.

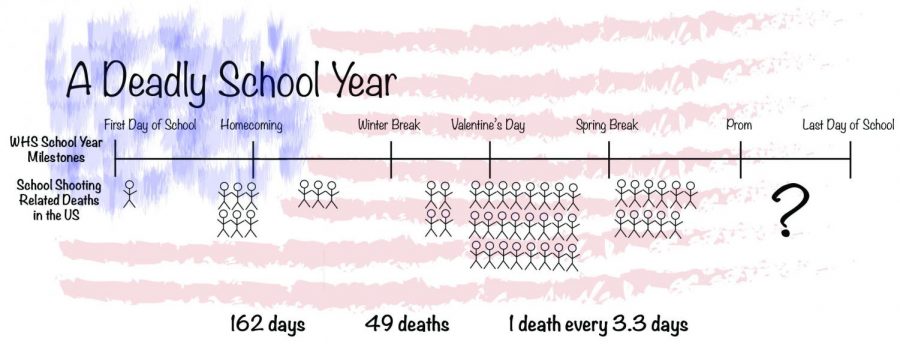

Last week’s school shooting in Santa Fe, TX, brought the number of school shooting deaths in 2018 to a total of 29, or an average of 1.4 deaths per week. The national conversation over gun violence has been ignited, and the halls of WHS are no exception.

Interviews with teachers, administrators and students paint a portrait of a school and community still struggling to come to grips with what has become a divisive issue. Safety protocols, administrators say, have been reviewed and they rank well above those in many other New Jersey schools. Yet troubling gaps remain—a tacit admission that no amount of preparation can create a perfectly safe school.

Unsurprisingly, some in the WHS community acknowledge that the Feb. 14 tragedy in Parkland, FL, has added to their sense of angst. Junior Lily Paone recalls the lockdown drill held only a few days after the Florida shooting. “It was so close to Parkland, so everyone was on edge,” Paone said. “When they called for a lockdown drill, even the talkative people got quiet.”

In Westfield elementary schools, most young students haven’t felt the same increase in anxiety that their older peers, and teachers, have experienced. Ms. Lori Swanson, a fourth-grade teacher at Tamaques Elementary School, said: “Most of the kids in elementary school have no idea about Parkland or Newtown or any other shooting. To have to explain why we do this is a little saddening.”

Swanson is not alone. “I think teachers now have the unwanted stress of being a security guard or a police officer,” said Mr. David Duelks, principal of Tamaques and coordinator of the Emergency Preparedness Committee in Westfield. “None of us signed up for this; we signed up to help and educate kids.”

Throughout the district, security changes have been instituted since Parkland to improve school safety. The town has paid StoneGate Associates, a consulting service for security, fire safety and emergency management, more than $6 million—the rough equivalent of 80 annual teacher salaries. StoneGate has installed security cameras, intercom systems and alarms. Duelks said StoneGate has called Westfield schools “above the curve” when it comes to safety.

One of the most apparent changes for teachers, administrators and students since Parkland has been the increase in police presence, particularly in primary schools. Swanson has noticed officers visiting Tamaques. “They come, spend a few hours, walk around and talk to the kids,” she said. “It’s been a comfort, but at the same time, intimidating.” Duelks is a strong advocate for this change and believes that it allows young students to build lasting relationships with the town police.

School Resource Officer Elizabeth Savnik shares Duelks’ feelings. “I interact with the students, staff members and daily visitors entering and exiting the school building,” she said. “In order to effectively learn and work within the school environment, it is essential for everyone to be safe physically and mentally.”

Despite the increased awareness, WHS students worry that some teachers may not be appropriately prepared for an emergency. Junior Katie Ceraso cites two separate occasions in which substitutes in her drama class were unaware of how to handle lockdown and shelter-in-place drills in the auditorium. Freshman Sammy Salz recalls a teacher who failed to close blinds and windows during a lockdown. An interview with Mr. Robert Steiner, a substitute teacher in Westfield for four years, revealed that substitutes are given information on how to handle drills but do not receive any specific training.

Mr. Jim DeSarno, assistant principal at WHS, explained that breakdowns in security are why schools must practice responses to emergency situations. After drills, an email is sent out to all teachers and staff outlining the issues that arose during the drill, clarifying what could be improved. “There are always substitutes in the building, and we try to educate them as best we can, but when we have students in the building who have done these drills many times, everyone can help,” DeSarno said.

Dr. Jamie Howard, director of the Trauma and Resilience Service at the Child Mind Institute in Manhattan, has been researching student anxiety caused by school shootings. On her website, Howard compares school emergency drills to those practiced in the military and believes that practice prepares students for real-life situations. “The more you practice something, the more you rehearse it, you lay the mental tracks so that you decrease the tendency to freeze in the case of a real emergency and you can go quickly into action,” Howard writes.

Westfield Public Schools are constantly looking to improve safety procedures. In a statement issued after Parkland, Superintendent Dr. Margaret Dolan said, “We will continue to review our safety procedures in order to do everything within our power to provide a safe and secure school environment for our students.” All administrators interviewed for this story expressed the same dedication to reviewing their emergency protocols in an effort to improve school safety.

Yet teachers and administrators acknowledge that it is difficult to completely secure any school. “There’s so many entrances and exits,” DeSarno said. But for him, safety boils down to one word: cooperation. Whether it is cooperation from the students by not letting in people who bang on the side doors or cooperation from the teachers by practicing emergency drill procedures, DeSarno remains impressed by the school community’s responses to drills and said that their preparation gives him a sense of confidence.

Teachers and administrators remain adamant that they are working hard to improve school safety throughout the district. “Our students are our No. 1 priority, and that is a common goal,” said Duelks. “We are constantly discussing security in our schools and our administrators do a good job of talking to one another. It’s impossible to predict if and when an emergency situation may arise, but I believe our staff and students are well-trained and prepared.”