Prideful and Prejudiced

Westfield’s Silenced Indigenous Narrative

December 20, 2021

When envisioning Westfield, images of cozy suburban residences and charming downtown shops immediately spring to mind, defining the town as the epitome of traditional suburbia. Westfield’s perceived glory centers around the success of its sports teams, its famed residents and traditions of excellence, but the upper layer of all-American pride is rarely scraped away to reveal the town’s darker past.

Hidden beneath a surface-level understanding of the town’s heritage exists the intricate story of the Indigenous civilization, a story that is often heavily distorted or ignored. Just as the white colonizers of the 17th century trampled the lifestyles of Native societies, modern understandings of the area’s past comparably flatten the importance of Indigenous history, reflecting disrespectful insensitivity to Westfield’s Indigenous inhabitants who faced unjust decimation and discrimination.

Prior to the establishment of the colonial “west fields,” the greater Westfield area was a lush forest defined by Lenni-Lenape encampments and migratory trails. According to a variety of local historical sources, Indigenous inhabitants populated areas today known as Ash Swamp, the Presbyterian Church and the Shackamaxon Country Club. Specifically known as the Sanhican people, the Natives presumptively lived in low, dome-shaped structures stably held by various stalks and branches.

The Lenape community traditionally traveled along the Minisink trail, which cuts directly through Westfield, to relocate between the southern shore and the northern mountains as the seasons changed. Many Indigenous sites in Westfield dotted the trail, most notably Fairview Cemetery as a burial ground.

The collection of historical views into Indigenous society undoubtedly confirms the presence of an established civilization with a vibrant culture; a culture that would soon be cruelly shattered by the domineering attitudes of white settlers.

While the English had already arrived to Indigenous land in a vision of self-absorbed grandiose, the year 1664 marked the beginning of dark, contemptuous treatment of Westfield’s Indigenous community.

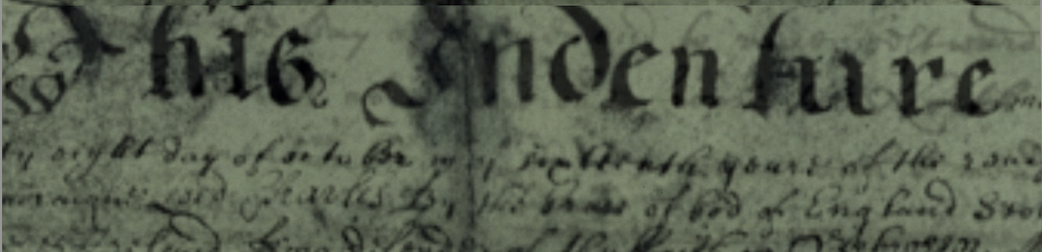

That year, Governor of New York Richard Nicolis facilitated a land deal between the Natives and the English. Deceitfully, the trade of Westfield and surrounding areas for the colonists in exchange for a sample of weaponry and supplies for the Indigenous peoples included a grave misinterpretation.

While the English understood the agreement as a land transfer, the Natives believed they purely sold hunting rights to the colonists, as the concept of owning land was nonexistent within Indigenous culture. The habitual lifestyle of the Indigenous population within the Greater Westfield area was forever altered, as that land was now under the ownership of John Baker, a colonist involved in the negotiation. In 1664, Westfield’s tradition of ignoring Indigenous voices had officially begun.

Modern examinations of Westfield’s history typically pay close attention to the town’s role within historical events and its evolution from being a quaint village to a bustling downtown.

However, little is discussed of the grotesquely discriminatory attitudes sewn into the town’s culture; Westfield’s colonists were not excluded from assuming a superiority complex in most aspects of criticizing the Lenape tribe. In fact, according to Westfield Historical Society Archivist Robert Wendel, even Indigenous burial practices were subject to scrutiny. As the elderly or ill passed away while the Lenape traveled along the trails bisecting Westfield, the frozen ground made laying the individuals properly to rest impossible, leading to the Natives instead carrying the cadavers until reaching somewhere warm enough to dig up the soil.

“[The Natives] would get two poles and string deerskin between the poles, and they carried the body with them until they could bury [it],” said Wendel. Oftentimes, that burial location was Westfield’s Fairview Cemetery, meaning colonists frequently witnessed the tradition and were overwhelmed by the stench of decaying bodies, leading Westfield’s colonists to specifically target the Lenape with cruel language. “The colonists were horrified by this — they used to call the Native Americans ‘the stinky people,’” Wendel explained.

As Westfield’s colonists continued to belittle the Lenape with discriminatory speech, weaving an aura of white supremacy within the town’s roots, the Indigenous people were gradually forced westward due to the expanding scope of the colonies. A continued understanding of Indigenous society now lay almost entirely in the hands of the colonists, but modern looks at English documentation of the Lenape reveal the construction of a distorted, dishonorable narrative.

Accounts of Westfield’s Indigenous community are found within a variety of local history books, but many are speckled with prejudiced language. Colonial journalists Jasper Dankers and Peter Sluyters, who are commonly referenced by many Westfield scholars, noted that the Natives were “dull of comprehension” and “slow of speech,” and such a perception has extended to the modern era. Charles Philhower’s History of Town of Westfield, written two centuries later, describes Westfield’s Natives as “very foul and dirty,” and Philhower himself later stated, “They just refused to change. That’s the only thing we’re certain of.”

Westfield has thus remained evidently constrained to an air of judgement and primacy toward the Lenape community, with evils of bigotry blurring the lens through which local historians may view the true importance of Native culture. Dismantling such a skewed outlook with an open mindset is necessary for the sake of justice for the town’s Indigenous inhabitants and greater clarity for future generations. While Optic did reach out to the present day Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation for information on Westfield’s contentious relation with honoring Indigenous history, the Tribal Nation did not respond to offer commentary.

It is important to mention that within the past century, Westfield has exercised a few events celebrating its Indigenous past; however, such attempts incur a standard of white colonization superseding the reality of Indigenous society. For example, during the opening ceremony of Mindowaskin Park in 1920, a cast of hundreds of residents portrayed the town’s historical evolution from the time of the Natives until World War I. The rehearsed show began with a scene of an Indigenous encampment with mentions of Lenape religious beliefs, traditions of diet and various forms of craftsmanship. The performance would undoubtedly take audiences aback in the modern era: white citizens donned stereotypically Native dress and promoted a whitewashed, warped view of Lenape society without input from Indigenous individuals. Both of these actions were executed entirely without shame as an audience of nearly 15,000 citizens proudly gathered to celebrate a deeply skewed and harmful view of the town’s history.

Westfield’s ignorant show of cultural appropriation further confirms that insolent tones are evident, even within the town’s cyclical retelling of Indigenous importance. Wendel maintains that the ceremony itself was likely not maliciously intended: “White people that painted themselves in Native American costumes thought that they were, in some degree, honoring the Native American presence in this area.”

Still, such an event should be subject to modern day criticism as an attempt to rid Westfield of a biased view of history and to provide greater acknowledgement for the town’s Indigenous society; the inappropriate reality of the gathering, however, is far from common knowledge.

On top of the reprehensible actions taken during the opening of the park, a parallel series of events occurred over 40 years later. During the Westfield Tercentenary Committee’s 1964 “Heritage and Destiny” pageant, white performers again portrayed the daily activities of the Indigenous lifestyle — hunting, fishing and canoeing — to reflect the Lenape origins of the land, but the script also made numerous references to Indigenous people as “redskins.” Although it can be argued that such an offensive term is simply a product of its time period, minimal levels of modern criticism recognize the prevalence of discriminatory language against the Natives. Refusing to accept the racist tendencies resting within Westfield’s culture instead enables the town to continue perpetuating modern-day oblivion to the true reality of the Lenape people.

Westfield’s lethargic attitude towards rooting out prejudice confirms that habits of ignorance still define the town’s culture. Few citizens actively understand that the pristinely manicured land they play golf on was once the location of a number of Indigenous homes or that the cemetery housing their deceased loved ones was once a site for the sacred burial of passed Lenape individuals. The construction of stately colonial-style mansions and debates regarding the evolution of downtown all presently act as modern-day extensions of colonial expansion drowning out Indigenous voices.

The history of the Lenape tribe is dismissed as trivial in comparison to more pressing local politics, and Westfield does not celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day or other forms of annually honoring the Lenape people. Together, these actions constitute a deplorable element of the town’s culture — a crass, ignorant level of pride that actively harms the overarching narrative to achieve acknowledgement for the importance of Indigenous history.

While this lack of awareness is concerning, a beacon of hope exists in our education system. Building an understanding of the people that came before us is critical in forming a complete identity and respectful existence for our next generation. We are fortunate to live in a town with a highly-regarded school system, but we can always be doing more to properly honor and inform about the people whose land we have built our lives upon.

Awareness of social issues has always been rooted in the passage of time; as new generations take control of the world, they build a more accepting society than the one that came before them. This is undoubtedly the product of progressively increasing accessibility to resources and education about cultures different from our own as technology has improved, because understanding breeds sympathy. Education in formative years is key to shaping the rest of a person’s life, which is why the role of the Westfield Public School District is such a difficult and crucial one to define. They chose to do it like this: “The Westfield Public School District, in partnership with families and community, educates all students to reach their highest potential as productive, well-balanced and responsible citizens who respect individual differences and diversity in an ever changing world.”

This mission statement directly defines the district’s idea of a citizen at their highest potential to be one that respects diversity. This is key to understanding how our curricula are designed, and reveals that the administration is aware of how Westfield schools are the first line of defense in filtering discrimination out of our society.

Fostering a culture of historical sensitivity is a significant undertaking, but necessary because of the content that is so often ignored in other parts of the country. A 2015 study by researchers at Pennsylvania State University found that 27 states did not even mention a single Native American by name in their history education standards, so Westfield students are lucky that effort is being made to more comprehensively teach about Indigenous culture.

Daniel Farabaugh has taught social studies at WHS for 17 years and has seen firsthand how education surrounding Indigenous culture has evolved. “When I was a kid, Columbus was taught as an unvarnished hero,” he said. “But it’s become more factually correct, with more use of primary sources, more bringing in authentic voices, and not speaking for the Native Americans, but letting them speak for themselves.”

Farabaugh emphasized how students have benefited from these improvements in education; they leave the classroom with a wider worldview when taught with varying perspectives. “More often, we have been using [Indigenous] language in the reading we bring in, and looking at their culture as part of not just something we talk about on specific days, but more as part of an inclusive narrative, because you can’t understand America without including this group of people.”

Understanding America is, of course, a significant undertaking. Instructors are given the support of a larger, defined curriculum as a guide to how to best inform students of these different points of view.

“Indigenous and Native perspective is frequently overlooked in the cultural interaction students have in their day to day lives. So when we look at the town of Westfield and how it was settled, we ask whose story we are telling and we try to look at it from a Native perspective and how events in history impacted those tribal communities,” said Westfield Public Schools Social Studies Supervisor Andrea Brennan.

Brennan detailed the structure of the elementary curriculum, explaining how each school year builds upon the understanding engendered in the preceding year. Diversity education begins in Westfield when students are in kindergarten, and a focus on Native American history is implemented starting in third grade and is largely based around comparisons to modern life, focusing on learning how the Native Americans lived. As students move to fourth grade, they learn more about the darker side of Indigenous history.

“That’s where we start to get into those tougher questions. There’s a question about what the real story of exploration is,” said Brennan. “We present both sides of that, not just the Native perspective, but also the perspective of the Africans who were being brought over to this new world, and how those things impacted European culture, the culture of Africans, as well as the culture of Natives.”

The fifth-grade instruction in history is particularly engaging, concentrating on the conflicts created over divisions of land and other resources, and Native perspectives are studied within these lessons. Starting students’ education of different cultures when they are young helps them to learn to appreciate a variety of history and traditions that they may not have been exposed to organically; this gives them a broader perspective of their place in history and allows them to develop into more well-rounded individuals. However, the current system, as relatively progressive as it is, is far from perfect. Even our leaders in education recognize this need for a change to create more awareness.

“I think that we could do a better job in teaching students about the Indigenous cultures and the Native tribes that were in Westfield and what happened to them,” said Brennan. “That’s not specifically written into the curriculum, and right now it’s more asking ‘what’s the history of Westfield?’ and ‘how was it created?’ and ‘how does the town provide services to its citizens?’ I was thinking about how much we should really emphasize that and where we could bring that in a little bit more. I think there are opportunities to incorporate that a little more explicitly.”

However, diversity education has been a contentious topic in recent years on a national scale, and even within our town itself. There has been aggressive backlash to an elective course based upon the tenets of critical race theory being offered at WHS. Power, Privilege, and Imbalance in American Society, designed to allow students to examine the history of the power imbalance tipped towards white supremacy in this country and how it has contributed to inequality in the present, was first offered in the 2020-2021 school year.

Despite consistent protests from a small, but raucous, group of parents in opposition, the course has become popular among the upperclassmen students it is offered to. The adverse reaction from residents is concerning to those who wish to further develop education; it raises the question of whether the town is as critically aware and progressive as it often presents itself to be or if it is rather a dangerously, pridefully white community at its core.

Due to this polarized environment that is against highlighting the negative aspects of history, it is even more essential that we expand the social studies curriculum to encompass a more nuanced approach to Indigenous history.

Yet, simply a mention of expanding diversity education inflames the passions of some of our more pugnacious denizens. Recent BOE meetings have made this clear, particularly in discussion of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) measure that was included in the Westfield Public School District’s goals for the 2021-2022 school year. The district defines the measure as a “framework to promote DEI in the areas of professional development, recruitment, selection and retention of diverse candidates, curriculum and curricular materials, community engagement and school-wide programming.” These objectives are in accordance with state-required guidelines for education.

“One of the main reasons we chose Westfield was for the strong public school system, and the district’s commitment to academics. Sadly, we seem to have lost our way,” said a local parent at the September BOE meeting. “The priority over the last few years has shifted from academics to social-justice issues… I’m increasingly concerned that the line has been crossed between curriculum and politics.”

These sentiments are dangerous; avoidance of the truth does not make facts cease to exist. Exclusion of information is technically deceit. Those in resistance to this type of diversity education are promoting lying by omission. The history of our country is not the clear-cut, good triumphing over evil, upholding of liberty and justice for all that those in opposition of teaching the facts would have our students believe.

Wendel described the misconceptions surrounding diversity education. “The problem is that people are misunderstanding what critical race theory is about. They are leaping to the conclusion that you’re trying to make white people guilty, but that’s not what it’s about at all,” he said. “It’s about understanding race relations, and how we can do better across all races. Some people don’t want this country to be a melting pot, but it is a melting pot, whether we like it or not.”

It is undeniable that white people have committed atrocities against other ethnic groups on the very land where so many choose to ignore it. However, references to the inhumane and abusive actions of our ancestors, particularly in that Colonial period that our residents are so proud of, would contrast the perfect, peaceful picture that the eyes of modernity love to paint. The culture of extreme ignorance present in our town must be dismantled.

The importance of Indigenous culture in Westfield did not end with the colonists in the 17th century. Westfield’s land will always be Lenape land. Breaking past the whitewashed, biased understanding of Native culture is necessary on multiple fronts: for the sake of individual morality, societal progress and historical reparations.

While generational changes to Westfield’s outlook on its Indigenous past will require a certain ethic of persuasion and keen attention to effective education, the power to take individual accountability rests within the hearts of every citizen. Recognizing the wrongdoings of the past and consistently learning from such mistakes to promote a brighter future is the most crucial step in the evolutionary process of doing everything possible to offer some form of justice to Native individuals.

The muddy reality of the past, however gruesome and disheartening, cannot be altered. The pathway to the future, must be paved with a consistent outpour of respect and acknowledgement for Westfield’s Indigenous past. It is merely the beginning of a long, increasingly sought-after journey toward some sense of justice.