Tradition of ‘Excellence’

An account of social comparison at WHS

December 3, 2018

WHS students are no strangers to high expectations, competition and rigorous academics. There is a compulsive need to know where you stand at all times. But at what point does this constant competition do students more harm than good?

WHS is one of the top thirty best high schools in the state, according to usnews.com. But in its efforts to maintain excellence, social comparison has become a widespread issue. Journalist, author and public speaker Malcolm Gladwell refers to it as relative deprivation, in which people evaluate their worth by comparing themselves with others.

“The more elite an educational institution is, the worse students feel about their own academic abilities,” wrote Gladwell in his book David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants.

“Students who would feel that they have mastered a subject at a good school can have the feeling that they are falling farther and farther behind in a really good school. And that feeling—as subjective and ridiculous and irrational as it may be— matters.”

Gladwell’s findings are supported by a 2007 study, “The Culture of Affluence: Psychological Costs of Material Wealth,” in which researchers noted that children of affluence are more likely to develop anxiety and depression, due to pressures to achieve.

Let’s consider one of Westfield Public Schools’ mottos: “Tradition of Excellence.” This message printed across nearly every WHS pamphlet, presentation and web page seems encouraging, but in reality, it sets a bar that students should always reach “excellence,” according to some high schoolers.

To junior Logan Calder, the motto reminds and expects “you to go on to a good college, [get] a good education and a good job.” However, the attainability of reaching this state of “excellence” is questionable.

“It causes people to think that they have to be the best and it leaves no room for slipping up because excellence is what you always have to strive for. It shows what the school environment is as a whole and that everyone has to be the best–but not everyone can be,” said junior Greta McLaughlin.

This motto serves as a lens for examining the mentality of our affluent town; there is a pressure for students to do better than peers and their parents and to amass more rigorous classes and extracurriculars than the student next to them.

For incoming freshmen, the competition and stresses of high school are familiar. “[The competition started in middle school because teachers] say high school grades count and so does everything on your resume,” said freshman Lili Demerdjieva. “I feel like kids want to cram it all in there so colleges will look at them.” And cram, they will.

This obsession is only amplified as more rigorous classes become available. “This year I took APUSH, and I felt like I was expected to take it because so many people took it,” said McLaughlin about the notoriously difficult and demanding course. Even after dropping the class, she mentioned, “I still felt like I wasn’t good enough because all these people are doing it and I’m not.”

Calder noted that it can “feel like a failure to go from Honors classes to regular classes” because “once you’re on the Honors path, you’re expected to stay there.”

The result: a toxic feeling of incapability and lack of intelligence for not subscribing to an academically rigorous regime. You should have, but you didn’t. So what about those who choose a different path?

Senior Morgan Eng is an artist at WHS. Despite her many achievements, including a Papermill Playhouse Rising Star Award for graphic design, she said, “Sometimes I feel like I’m missing out because I’m not taking [the Honors and AP classes my friends are taking].”

“I sometimes think that I didn’t take hard enough classes, or I didn’t work hard enough to get that A, or that my standardized test scores aren’t high enough, because of how high other students have reached,” Eng continues. “And sometimes that scares me that I won’t get into a good school compared to my peers.”

Fears of inadequacy and inferiority do not only belong to the students, but also parents. An anonymous junior, Student A, explained: “My parents put so much pressure on me to take certain classes and do certain things … that’s why I took APUSH. [My dad] said ‘Well, if you want to get into competitive schools…’”

The general Westfield definition of a “good, competitive” school equates to an Ivy League or one of its cousins. “If I were to label good schools, I would say it’s the Ivy League schools that are really good, and bad schools are community colleges,” said freshman John Gonzalez.

The college bumper stickers, sweatshirts and chatter that begins in ninth grade have infiltrated students’ minds as to what the “right” college is; the pressure to be accepted into elite universities can often mean competition among classmates and friends.

As Director of Counseling Maureen Mazzarese said, “If you’re running a race and you want to get to the finish line, you are always looking at who’s coming up behind you.”

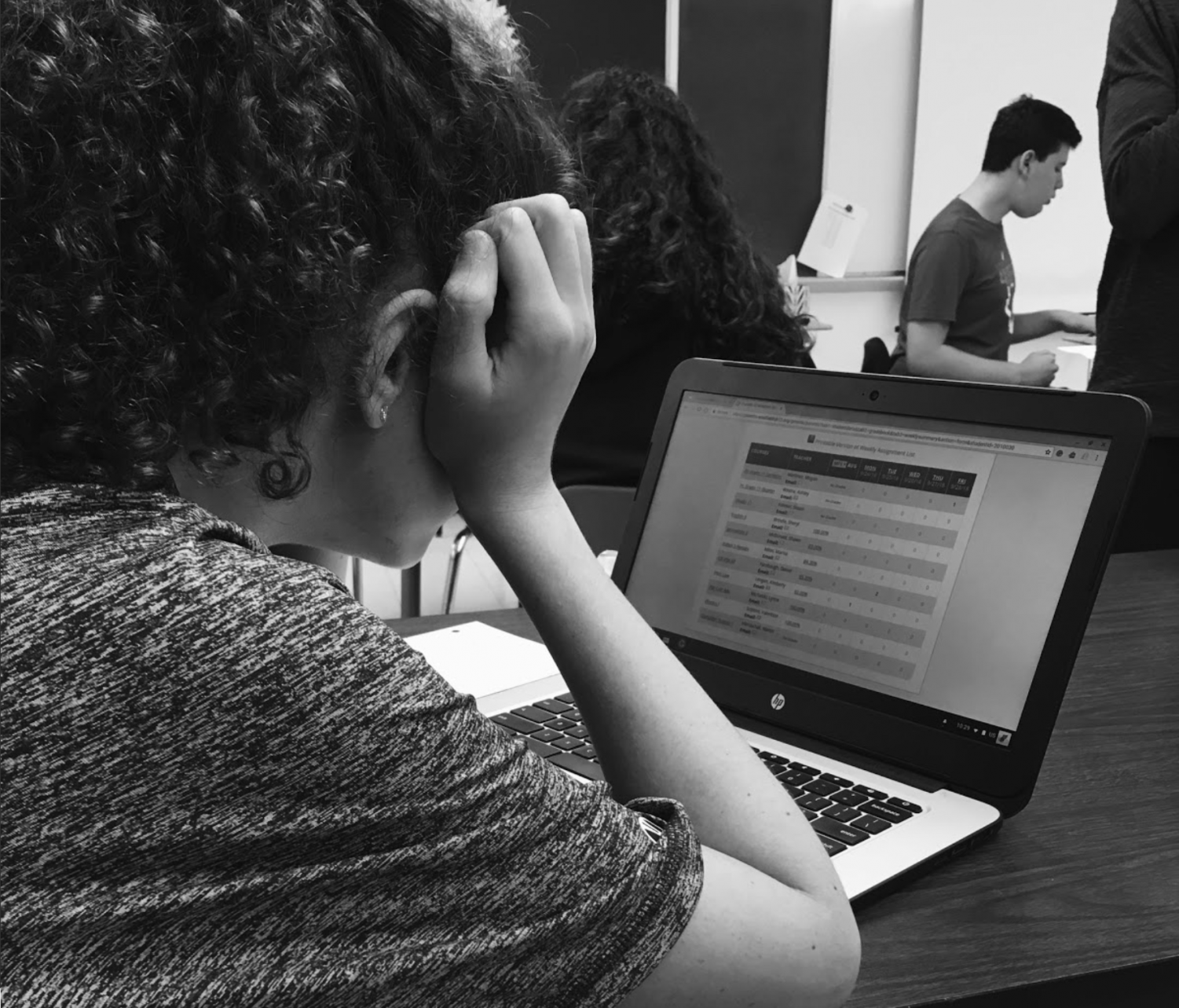

In this race to top universities, the pressure parents put on their kids is amplified by the Genesis grade portal. English Teacher Darren Finkel shared how students’ continual access to their grades “breeds an unhealthy attitude about how they’re doing in a class because of the constant concern about what their grade is and if it fluxuates modestly, it can be cause for panic.”

One anonymous parent even noted that when she talks to other parents, “they seem to know the grade of each and every assignment.”

Calder said that his mom is “pretty relaxed” with grades: “She’ll look at the grade portal once in a while, and say, ‘Why’s there a B in there?’ and if I say, ‘Look, there was a tough test, I’m working on it,’ she’ll leave it at that.”

Bs on the grade portal can be troubling to the eyes of parents and students, which invites the question: What is so wrong about a B? Earning a B is characterized as a “high quality achievement” on WHS report cards, but it is often translated to failure in the typical WHS mind. An A, or “excellent achievement,” is what you should get.

Parents certainly mean well – it’s only natural that they want the best foundation for their children’s success. But a formulaic, one-size-fits-all approach to reach success, as defined by the characteristics above, can be destructive to a student’s self-esteem and authenticity.

Dr. Jacquelyn Doran Cunningham, a psychologist at Westfield Mental Health Specialists LLC, who specializes in child and adolescent behavior, wrote in an email: “A problem can occur when students associate their self-worth with their accomplishments (‘I am my accomplishments’) rather than viewing their achievement as only one of their many characteristics… students not achieving at levels they feel are satisfactory (even if not satisfactory is an A-) may experience feelings of inadequacy, low self-esteem and depression.”

Mazzarese would often sit with students who struggled with this mentality and would ask students to “tell me who you are not what you do. And they would sit in silence for minutes at a time … I try hard in all my conversations with everybody [to focus on] qualities rather than statistics.”

In an age of statistics, however, it’s easy for students to rank themselves amongst each other. “When you get a test back everyone asks ‘what’d you get, what’d you get, what’d you get’ and it’s kind of like a competition,” said senior Casey Cohen, whose anxiety was worsened by WHS’s atmosphere. “I mean it’s not kind of like, it is a competition to see who can get better grades.”

Similarly, McLaughlin reflects on her sophomore year, when she almost had a mental breakdown. “I used to get a lot of panic attacks from school and it’s kind of stupid because when you think about it: It’s just school, it’s not a life or death scenario- but it feels like that.”

Being a well-rounded student is difficult when excelling at school feels necessary for self-worth. So some students participate in activities, interested or not, to play the part of the well-balanced citizen. Many students’ genuine interests and personality developments can be surrendered for what they believe a college wants.

“I’m part of the Environmental Conservation Club at the moment – primarily because I think it’s going to look good on the college application,” said an anonymous junior, Student B.

“I was interested in [the Transition Program] beforehand, but I heard that colleges like to see it, so that was a motivating factor of why I decided to pursue it.”

Student A added, “I do Model UN and I hate it and I do it because I feel like I have to.”

You don’t have to, but you should.

****

In our conversation with Mazzarese we talked about the tyranny of the shoulds: I should do this, because if I don’t, I failed. This inevitably fuels social comparison and subsequent student stress.

We can change this mentality through language.

Mazzarese said to “replace the ‘shoulds’ with ‘I might’ and ‘I’ll try’; if you get it, great, and if you don’t – well what’s the takeaway?” With this mindset, students are more inclined to explore a new avenue that they are interested in, building resiliency, and not because they are pressured to do so.

In the classroom, teachers can be part of the solution. “Since I started [acknowledging wrong answers], participation has increased noticeably. I did this because so many students have confided in me that unless they think they have the right answer they will not raise their hand in class,” said Health Teacher Susan Kolesar, who has a sign in her classroom saying “I love wrong answers.”

Shifting the focus from others’ achievements to your own potential is instrumental in embracing one’s own abilities. School doesn’t have to be a competition. After all, we are here to learn.

Writer’s note:

As seniors, we’ve experienced and witnessed social comparison and its reverberations in the student body. Through countless interviews with students, parents and administration, many were relieved that this topic was finally being addressed. After a month of researching, we realized that this is a mission that everyone can work to solve – but it’s our choice if we want to be the agents of change. You are more than your grades, transcript, or future college. You are enough.

-Nicole Boutsikaris and Kayla Butera

Susan Kolesar • Dec 3, 2018 at 11:18 pm

Great topic. Great article. I hope it is the beginning of a bigger conversation. In my humble opinion, mental health must come before grades.