‘Rad Women’ of WHS

Why you need to take WHS’ Women’s Studies course

Photo Fiona Gillen

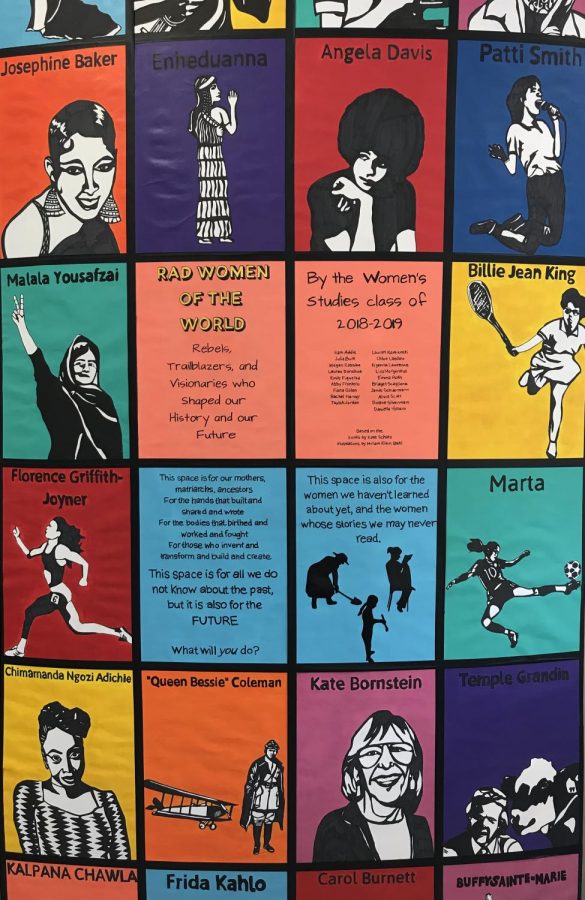

The mural made by this year’s Women’s Studies class, mimicking the artwork of The New York Times’ best selling books, Rad American Women A-Z and Rad Women Worldwide, written by Kate Schatz and illustrated by Miriam Klein Stahl.

It’s sixth period in Room 234, and it smells like Sharpies, wood glue and Smartfood popcorn. Sixteen girls are hunched over their desks, paint brushes in hand, meticulously outlining portraits of civil rights activists, athletes, scientists and astronauts—all of whom are women. Angela Davis, Rachel Carson, and Kalpana Chawla. Odetta Holmes grips her guitar as Billie Jean King swings her racket. Each woman has a different story, but they’re unified by the same obstacles—and I hadn’t heard of half of their names before I stepped into that room.

Welcome to WHS’ Women’s Studies course, pioneered in the 2016-2017 school year as a semester-long English elective for juniors and seniors. It’s advertised as a class that challenges students to evaluate the experience of women in American culture. Women’s Studies teacher Rebecca McGrath said that her primary goal is to support her students in questioning the world around them. My semester in Room 234 taught me to do exactly that.

Whenever I talk about Women’s Studies (which is, admittedly, a lot), I’m often asked if there’s a “Men’s Studies” course as well. My candid response: that’s every history or english class I’ve taken. The curriculums of these courses, by no fault of their teachers, favor men—mostly white men—over women time and time again. Ida B. Wells’ reporting on lynchings is overshadowed by Thomas Edison and Sherlock Holmes. Alice Paul’s National Women’s Party is lost somewhere in between World War I and Prohibition. Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique is pushed aside for JFK assassination conspiracies and Ken Kesey.

Women’s Studies moved my focus away from the power of the patriarchy. We dedicated time to learning about these women in history, from Sanger to Ginsburg to Steinem, and it was then that I discovered the female role-models that I’d been deprived of for so long.

Sixth period became a family as my classmates and I bonded through sharing stories and uncovering similar experiences. Our class worked together to learn and grow from what we shared, supporting each other along the way. I was given the tools to recognize and call out discrimination while feeling empowered to do so. Room 234 filled in the holes in my education in ways that have and will impact me for the rest of my life.

Women’s Studies isn’t just about women. A large part of the class focuses on understanding intersectionality, or recognizing that women’s issues are conjoined with issues of religion, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class and more. All aspects of identity must be taken into account when examining systems of oppression—which is exactly what this course does.

Women’s Studies also isn’t just for women. This is a common misconception, and a very dangerous one. Misogyny can stem from a lack of education, and both boys and girls need to learn about the countless brilliant, fearless and powerful women who have accomplished as much as any man. They need to learn to recognize privilege—their own and others—because calling out misogyny and discrimination should be the duty of a man as much as it is mine as a woman. Feminists demand equality which, by definition, includes men as much as women. Women’s Studies is no different in this inclusion.

The middle panel of my class’ final mural reads: “This space is for all we do not know about the past, but it is also for the future. What will you do?” An easy first step in answering this important question: take Women’s Studies.